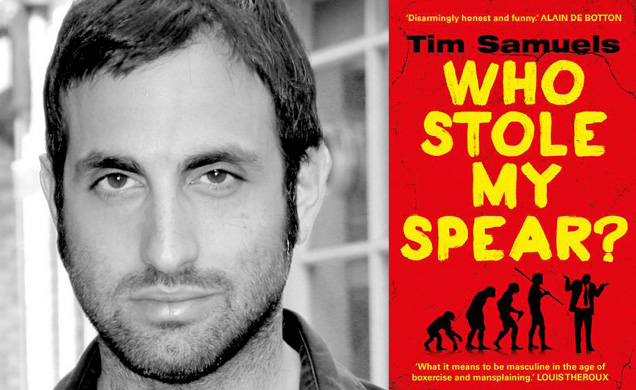

Lost Your Spear?

When you witness the plight of millions of refugees or read some of the vicious anti-women posting online, you might wonder whether we need another book from a Western male about how tough his lot is. You’d be right.

But Tim Samuels, the award-winning documentary maker and presenter of Radio 5’s Men’s Hour is far more subtle and interesting than that. His excellent new book Who Stole My Spear talks of men trapped in bodies more suited to living in caves yet required to have it all, be it all and still not cry in public.

Why did you write the book?

Having done Men’s Hour and some documentaries in the space, I could see that when you put all the pieces of the jigsaw together, there’s a fundamental question around masculinity. Good masculinity is such a powerful force yet in such short supply.

Male power is so taken for granted that you don’t think of masculinity as undernourished. But when you look at men’s mental health and suicide, and the link with the recession, at boys falling behind at school, at young men joining Isis for some sense of belonging, at the rise of Donald Trump among blue collar men. Even the number of penis enlargements is rocketing. These all point to a bigger picture of masculinity as a primal force that we ignore at our peril.

When it’s being harnessed well, it’s a great thing. But when it doesn’t have a good outlet, when men can’t even do the basic economic stuff of providing, it becomes a negative, self-destructive force. Men dominate prison populations. There’s homelessness, alcohol. It becomes a negative force within, driving depression. If you don’t take masculinity seriously, you are overlooking a really powerful force in society.

How would you define good masculinity?

We have fundamental needs: to feel productive and to belong. It’s how to vent testosterone in a positive way. A negative way could be to start a fight, a positive way could be a martial art.

Compared to our male ancestors we’re not facing being called up for war but they had a more fixed place. They knew what they were doing. They had jobs for life. We have hunter-gatherer bodies but we have sedentary lives – physically, we’re out of kilter with how we’re designed. Good masculinity is getting back in touch with our bodily designs.

But it’s more than going for a jog.

It includes basic physical exertion but it’s also about belonging, meaning and productivity. Work is very central to men’s identity. If you tie all these important things to jobs that are insecure, rigid and hierarchical that leaves men in a very vulnerable position.

Were our fathers and grandfathers more fulfilled?

It's difficult in hindsight to know but at the time of, say, the American Civil War, nine out of ten men were self-employed shopkeepers or farmers not small cogs in big machines with line managers and open plan offices.

Better an open plan office than the pit?

It may be be better for lifespan but not for sense of meaning and belonging. There’s not a lot of poetry about open plan offices or call centres.

Perhaps men in previous generation suffered from frustration on a magnitude we don’t know about because they never articulated it but we do know there is a serious mental health problem for men today. Suicide is the most visible tip. In the past men were more likely to end up in the trenches but they weren’t racked with same existential pressures.

Is it men who need to change or society?

Workplaces can change. Big companies can take responsibility for those who work for them. Perhaps office workers should start the week with manual labour Mondays, doing something that benefits society, carving out space to get testosterone flowing in a good direction.

Work saps so much of our life and soul. Companies should ask how to make their workers happier and more productive.

But you’re doing work you enjoy.

I find the freelance thing difficult sometimes and question it. When I was BBC staff, I was more anchored. I don’t feel my masculinity is getting a good run out. Writing a book is isolating. My human contact is to overstay my welcome in the post office!

What do you do about it?

I know what I should do and what I actually do. There's a difference! When you’re writing, it’s about how do you remain sociable, have human contact. Writing feels unnatural from a male point of view. But if I was married and had a family, I would probably feel more balanced when writing.

Is this more about the economy and poverty than about masculinity?

Men’s biggest enemy isn’t feminism, it’s the economy. The hyper concentration of wealth means that providing is far harder than it should be. Money is not circulating. People are stuck in jobs trying to keep up with property prices. The modern economy has made it difficult for men. That’s the biggest factor given that, for better or worse, there is a real link between men' s wellbeing and what they do for a living.

Do we need to be defined by what we do?

The people who are happiest are those doing something that benefits others and isn’t about the money but in this economy that’s difficult to do. The economy gives us less opportunity for passionate, meaningful jobs. Even if you define yourself by, say, being a good dad, you need enough work to make ends meet. If you do job that makes you miserable, it’s hard to be a loving dad.

Whether it is self or society, men are more pressured by the need to provide and more affected by work. That doesn’t mean women aren’t affected just that it has more catastrophic effect of men when it goes badly.

How do you avoid this discussion turning into the misogyny we see online and hear from Donald Trump?

Donald Trump has tapped into a blue collar, downwardly mobile anger. I’ve talked to some of these guys. They’ve lost job security, can't make ends meet and feel emasculated by it. They turn the anger and fear outwards and lash out at women, immigrants and trade deals.

They see in Trump a father-like figure. A powerful alpha male who blames other people – not me – and will fix it. The same people with a different mindset could be Bernie Sanders supporters blaming a rigged economy for these problems.

What’s your advice to men who want to express masculinity positively?

In the book, I talk about how we count calories and steps but more importantly, we should count good masculinity: count our spears. We should do something productive unrelated to work, take physical exercise, sing in a crowd, spend time with male friends – there’s checklist in the book.

We should see spending time with male friends as essential to wellbeing. It’s not a luxury. Research suggests it is good for the immune system and mental health. For me, it’s very therapeutic. We should carve out time for this.

Is that more difficult in the digital age?

Seeing what friend posts on Facebook isn’t same as sitting with them in the pub. It recentres and rebalances you. Men today have lost sight of that. I have friends who have to plan three months in advance. But not doing it places too much strain on your relationship, expecting your partner to deal with all your emotional needs.

Through history, we’ve spent most of our time with other men. All of a sudden that has gone except for stag does when people go crazy and cram too much testosterone into a single week-end.

What should organisations like the Men’s Health Forum do?

It may be unfashionable but there is a need for politicians to take the plight of men seriously. Some men may be doing well but a lot aren’t. It’s like poker – at the moment there are a few big winners and not enough people who are slightly up. iI you want to address boys falling behind, address crime and alcohol then we need a male dimension to policy. This is not anti-equality. It’s not a zero sum game with women.

I think we could come up with policies that see more boys doing well at school and reduce reoffending and guys turning to violence, booze and even to dangerous politics.

it needs smart, counter intuitive thinking and working with companies. They have the levers of control. Ask them about absenteeism, sickness. Who wouldn’t want happy, productive, fired-up men in their workforce?

You made a documentary about porn. How does that relate to this?

Today’s hardcore porn on tap is not something that helps men in their relationships. It is very toxic. It damages happy relationships with something fake. It’s a barrier to intimacy. When you have young kids getting their sex education from hardcore porn, it’s worrying.

You talk about reasonable expectations.

I think we have to try somehow to not staple ourselves to unrealistic expectations. The gap between expectation and reality can really affect mental health. Everyone has these expectations that they can be anything they want but it isn’t true. Porn, airbrushed models and Hollywood films give us expectations that most men before us didn’t have. Their view of attractiveness would be based on 100 people in their village. They could make far more pragmatic, realistic relationships.

It’s not railing against modernism. It's that we’ve overevolved lately. We have such expectations and pressures. Look at boys at school today and the rates of mental health problems and eating disorders. A lot of pressures are taking their toll.

Society has changed quicker than we have?

We need to recalibrate to recognise masculinity is powerful for us as men and for society. We’d all benefit: men, women and children.

- There's more about Tim, his book and his work on his website.

|

The Men’s Health Forum need your support It’s tough for men to ask for help but if you don’t ask when you need it, things generally only get worse. So we’re asking. In the UK, one man in five dies before the age of 65. If we had health policies and services that better reflected the needs of the whole population, it might not be like that. But it is. Policies and services and indeed men have been like this for a long time and they don’t change overnight just because we want them to. It’s true that the UK’s men don’t have it bad compared to some other groups. We’re not asking you to ‘feel sorry’ for men or put them first. We’re talking here about something more complicated, something that falls outside the traditional charity fund-raising model of ‘doing something for those less fortunate than ourselves’. That model raises money but it seldom changes much. We’re talking about changing the way we look at the world. There is nothing inevitable about premature male death. Services accessible to all, a population better informed. These would benefit everyone - rich and poor, young and old, male and female - and that’s what we’re campaigning for. We’re not asking you to look at images of pity, we’re just asking you to look around at the society you live in, at the men you know and at the families with sons, fathers and grandads missing. Here’s our fund-raising page - please chip in if you can. |