In the UK, men are far more likely to die young than women - 40% of males die before the age of 75 compared to 26% of females. Indeed, even today, one man in five dies before he is 65.

Men are three times more likely to die prematurely from heart disease, three times more likely to die from suicide and, if you exclude the gender-specific cancers and breast cancer, 67% more likely to die from cancers that affect both sexes.

The truth is that as we break more and more data down by gender, we are learning that there is a gender dimension to nearly every health problem. It should be stressed that increased gender-sensitivity in policy-making and health care would benefit women as well men. And so, the nation as a whole – to say nothing of the NHS’s much-pressed budget.

Lack of gender-sensitivity worsens outcomes

Agenda, a charitable alliance for women and girls at risk, recently reported that mental health services across England are not adequately considering the needs of female mental health patients. A freedom of information (FOI) request had revealed that only one NHS Mental Health Trust, out of the 35 who responded, had a women’s mental health strategy. The Men’s Health Forum found much the same when it examined local authority Joint Strategic Needs Assessments. Less than one in five were even adequately recording data by gender, let alone acting on it. This lack of gender-sensitivity worsens outcomes for both sexes.

If we look at two of the major challenges in health care today, obesity and diabetes and mental health, the gender dimension in presentation – and hence the need for a gender dimension in our response – is clear.

Although levels of obesity are now much the same (men have been catching women up here), men are more likely than women to be overweight (65.3% of men compared to 58.1% of women). Men are also more likely to have diabetes - 8.7% of adults males have the condition compared to 6.5% of adult females. And are considerably more likely to present with complications of the disease. Two-thirds of those with foot ulcers are male.

Undiagnosed male mental health problems

With mental health, the picture appears, on the surface, more nuanced. According to the Mental Health Foundation, women in England are more likely than men to have a common mental health problem and are almost twice as likely to be diagnosed with an anxiety disorder. They also say that 10% of mothers compared to 6% of fathers have mental health problems at any given time. But - and it’s very big but - at least three-quarters of suicides are male. The implication is that there are a lot of undiagnosed male mental health problems out there.

Again and again there is a mismatch between the way the problem breaks down in terms of gender and the patient gender-balance in the services offered. So, for example, while men are more likely to be overweight, a Men’s Health Forum FOI request found men were only 21% of those on local authority tier 2 (lifestyle intervention) weight-management programmes. Similarly, while three-quarters of suicides may be male, two-thirds of IAPT (Improving Access to Psychological Therapies) referrals are female.

What can GPs do?

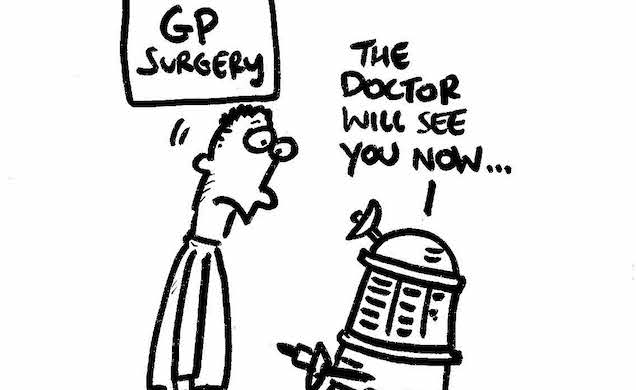

How can GPs make a difference? After all, you may be saying, I never see my male patients. Certainly, there is a perception amongst GPs – as there is amongst policy-makers and the general public – that unlike women, men don’t go to the doctor.

There is some truth in this. The latest GP Patient Survey (July 2016) suggests that men are twice as likely as women never to have seen their GP. But look closely and the real difference is among men and women of working age. Retired men go to the GP pretty much as often as women of the same age.

So the challenge for GPs is to reach men of working age in the first place and then to move them on to any other services (IAPT, weight management or whatever) that may be necessary.

Don’t underestimate the reluctance of the working male to go to the GP. In a Men’s Health Forum survey only 61% of men said they would go to see their GP if they had blood in a stool, only 54% if they were coughing up blood and only 28% if they had a persistent cough. Cancer symptoms all. When it comes to mental health, 34% of men would be embarrassed or ashamed to take time off work for mental health concern such as anxiety or depression (compared to 13% for a physical injury) and 38% of men were concerned that their employer would think badly of them if they took time off work for a mental health concern.

There is some evidence that the latter fear is justified. We’ve all heard of the gender pay gap but there is a mental health pay gap too. Men living with depression or anxiety earn 26% less than men who don’t experience these conditions. For men who experience panic attacks, the gap is 42%. (You might imagine that women living with these conditions would face a double whammy. True, there is a gap but it’s far narrower than for men: women with mental health conditions earn on average 10% less than those without which perhaps reflects the lower starting point for women earners.)

Fear of taking time off work coupled with fear of wasting the GP’s time multiplied by the nagging worry in the back of the mind that it ‘might be something serious’ is a strong cocktail. But there are things you can do.

- A Men’s Health Forum FOI request uncovered only 2 CCGs with a lead for men’s health. So assign a lead of your own to collect and regularly review gendered performance data for every area of the practice’s work. Train your organisation to understand men’s health issues and deal more effectively with men – with special attention to stigmatised problems like mental health and eating disorders.

- Remove the structural barriers. The more you are available outside ‘normal’ working hours the better.

- Think about the ‘user experience’ at your surgery. What is the route patients need to take to see you? This will involve looking at everything including your outreach, your systems, your non-clinical staff, your waiting area (its appearance and facilities) and looking at the barriers that each may present to all groups of patients including working men. Ask members of those groups what would help.

- Think about the requirements of working people when it comes to your procedures. Working people can’t phone up early on the off chance, they need appointments they can book. Similarly, if you offer telephone appointments (and you definitely should), working people can’t always take a call at a time of your convenience – again bookable times would help.

- Think about how you can do more online. The Men’s Health Forum’s Man MOT service which enabled men to text chat with a GP in the evenings proved there is an enormous demand for this sort of service. Online ‘consultations’ whether through chat or simply email can, like telephone appointments, be enormously useful for triage: giving ‘permission’ to those who need to see a GP to do so and reassuring those that don’t or who can be more easily helped via another service such as the pharmacist.

- The Man MOT GPs will tell you that you can talk to far more people in one hour via email or chat than you ever can in person in surgery. With more patients and less money this is something that practices can simply no longer afford to put off.

- How much outreach do you do? The NHS is enormously popular, as the campaigns that spring up when any hospital is slated for closure prove. Piggy-back on this. Recruit some friends of the practice: volunteers that spread the word. Make one or more a men’s health champion and pair them up with a health professional. You don’t have to run health checks in the local pub – although it would be great if you did – but at least make sure you're at community events. Participate actively in events designed to raise health awareness – Men’s Health Week, for example, which runs in June in the week leading up to Fathers’ Day.

- Finally, the best way to get anyone into your surgery: invite them. Look at the various reasons you invite people to attend the surgery such as screenings or vaccinations. How many of these people are male? Look at the more informal events like open evenings and the gender breakdown is probably much the same. Invite men in. Those who haven’t had an NHS Health Check, for example. (Men’s Health Forum research found that men were only 44% of NHS health checks and 15% less likely to respond to invitations. So ask again.) And be opportunistic when you get them there. This may be as much about making sure they understand that they can and should see you, that fear about wasting your time is misplaced, as about quizzing them on their smoking or drinking.

In the current climate, GPs might think the last thing they need is more patients coming in. However, looking at the way you operate in a way that removes barriers for as many groups as possible while providing as wide a range of access options as possible will mean that the people you do see are those you need to see when you need to see them. That is better for everyone including the practice manager’s budget.

- A fully-referenced version of this article by Jim Pollard first appeared in Practice Management: Across the gender dimension (Nov/Dec 2016)