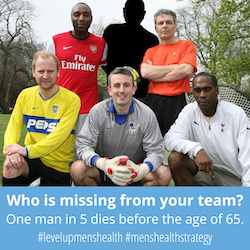

Across the UK, men’s mental and physical health is unacceptably poor – with around one man in five dying before the age of 65.

COVID has worsened the situation with completely disproportionate effects amongst men. Many services are failing to reach men in time, especially working-age men, even though there are ever more examples of how services can be designed to reach and engage men more effectively.

The lesson from other countries is that introducing a men’s health strategy alongside the government’s planned women’s health strategy can change this. This document lays out the case for change. (You can downlaod a PDF with all the references at the foot of this page.)

Even today, too many men are dying too young

In 2020, 19% of UK male deaths – around one in five – were before the age of 65.

Men are:

- 75% of deaths from suicide – with suicide the biggest cause of male death under 50

- 76% of premature deaths from heart disease

- 43% more likely to die from cancer

- 63% of premature deaths from COVID-19

- 26% more likely to have type 2 diabetes and 68.5% of diabetic amputations

- 66% of alcohol-related deaths

In September 2021, the ONS reported the first decline in male life expectancy since the 1980s.

Society pays a huge cost for this – with 676,000 years of life lost every year in the working age male population in England and Wales (16-64), mostly through avoidable premature mortality.

Aside from the emotional and social consequences, this imposes huge costs in health costs, sick pay and welfare benefits and the economic and tax losses of lives unnecessarily cut short.

|

Working years of life lost amongst men in 2020

- Cancer: 101,000 years

- Suicide: 76,000 years

- Heart disease: 66,000 years

- Accidental poisoning: 61,000 years

- Liver disease: 45,000 years

- Covid-19: 41,000 years

- Strokes (cerebrovascular disease): 17,000 years

- Road accidents: 17,000 years

|

Unequal risk: the need to level up men’s health

The state of men’s health is also deeply unequal. It is dramatically affected by levels of deprivation.

- Male life expectancy in Bloomfield ward in the north-west town of Blackpool is 68.2 years.

- In Warfield ward in the south-east town of Bracknell Forest, it is 90.3 years: a 22-year difference.

Comparing the lives of men in the most and least deprived 10% of areas of England, there is a 9.4-year gap in average life expectancy and a 19.0-year gap in healthy life expectancy.

Men’s health is also disproportionately impacted by social exclusion. In the UK, while male life expectancy, on average, is 3.9 less than female life expectancy, the gap between men and women widens with increased deprivation, reaching 4.6 years in the lowest deprivation decile. Neither are men a homogenous group, some of those who are hardest-to-reach of all, such as rough sleepers and reported victims of modern slavery, are groups comprised overwhelmingly of men.

Services fail to reach and engage men soon enough

Health services engage men, especially working age men, less effectively.

Men are 32% less likely to visit the doctor – particularly during working age. Despite being 75% of suicides, men are only 34% of those referred to IAPT. Men are 76% of premature deaths from heart disease and the majority of those with Type 2 diabetes, but a minority of those undertaking NHS Health Checks, despite its effectiveness in detecting both conditions. This lack of engagement not only means that men’s all-round wellbeing is under-supported by regular health check-ups, it can result in much more serious issues going untreated for longer, sometimes until it is too late.

COVID: a perfect storm for men’s health

COVID has brought all of this into sharp relief – men are 65% of those hospitalised from COVID and 61% more likely to die from COVID. The inequalities between men that we have seen in other areas have been reflected in COVID, with, for example, English men from the ‘Black Caribbean’ ethnic group were 2.6 times more likely to die from COVID as white English men during the first wave of the pandemic, and 4.2 times as likely to die from COVID as white English women [23]. Men’s behaviour, compliance and response to government guidelines on mask wearing and social distancing have been different. The health system has also been less effective in engaging with men – with lower vaccination rates amongst men in every age group – particularly younger men.

Better for men and better for women

The Government’s recent commitment to Women’s Health Strategy is a breakthrough in recognising the need for gender-informed health care. Many of the conditions they highlight which affect both men and women are those where a gender-blind approach is worse for women and worse for men.

As an example, the Women’s Health Strategy has noted that women in the UK have more than double the rate of death in the 30 days following a heart attack than men – and rightly calls for action to address this.

At the same time, lack of a gender-informed approach means that men’s care is also suboptimal. 15% of men have untreated high blood pressure vs. 10% of women – at least in part through less effective engagement from primary care and the NHS Health Checks programme.

As the 2017 GenCAD project noted: “Women and men get different forms of heart disease at different ages, with different symptoms and may need different types of prevention and therapy”. A gender-informed approach to tackling heart disease will lead to more effective action in tackling all these issues. A gender-blind approach will not.

And the same applies in a wide range of other areas: whether it’s mental health, weight management, diabetes or cancer, men and women both benefit from a gender informed approach. There has been significant growth in voluntary sector male-targeted initiatives to tackle these issues like Men’s Sheds, Man v Fat Football and Andy’s Man Clubs, but huge opportunities remain for the statutory sectors to target, tailor and adjust their services more effectively.

In 2019, the Women and Equalities Committee recognised the benefits of a gender-informed approach following their inquiry on the mental health of men and boys. Whilst the 2019 General Election truncated the inquiry, one of the recommendations the committee chair made to the Government following the inquiry was: “The Department of Health and Social Care should give serious consideration to creating and implementing a National Men’s Health Strategy, like those launched in Ireland and Australia.”

International lessons: a men’s health strategy can work

In response to these pressures, more and more countries are implementing gender-informed health strategies - with the following countries putting in place men’s and women’s health strategies or action plans:

Men’s Health Strategy is also getting increased international attention. In September 2018, following the adoption by WHO Europe of a women’s health strategy in 2016, UK Government representatives accepted the principle of a men’s health strategy when they, alongside representatives from other countries across Europe, endorsed WHO Europe’s “Strategy on the health and well-being of men in the WHO European Region”.

And these strategies work. Ireland, Brazil and Australia have renewed their strategies. Since 2008 when Ireland introduced its Men’s Health Strategy, Irish men’s life expectancy has increased from 76.8 (2005-07) to 79.6 (2015-17) and the life expectancy gap between men and women has declined from 4.8 to 3.8 years. Over the same period men’s life expectancy in the UK has fallen behind Ireland, going from 77.1 to 79.2 and the life expectancy gap has only fallen from 4.3 years to 3.7 years. An independent evaluation of the first Irish health strategy in 2015 stated:

The NMHPAP (National Men’s Health Policy and Action Plan 2008-2013) has made a significant and important contribution to making the issue of men’s health more prominent and providing a framework for action

A DFID funded assessment of the Brazilian Men’s Health Strategy noted:

In Latin America, PNAISH (National Comprehensive Healthcare Policy for Men) has generated visibility and vibrant responses among government, civil society, and academics on men’s health, masculinities, and gender, in the face of ongoing tensions among biomedical, gendered, and sociological perspectives. … The policy is helping to mobilise and provide evidence to a growing field around men’s health.

Growing coalition of support

Current supporters include the Men's Health Forum, the Patients Association, UK Men's Sheds Association, Prostate Cancer UK, Rugby League Cares, the Men & Boys Coalition, Orchid (fighting male cancer), CHAPS, Mengage, Black Men's Consortium, the Fatherhood Institute & the ManKind Initiative. Leading scientific and academic figures include Professor Roger Kirby, Professor Alan White and Professor Anne-Marie Bagnall.

In addition, the All-Party Parliamentary Group for issues affecting Men & Boys, chaired by Nick Fletcher MP, is currently reviewing the case for a UK Men’s Health Strategy.

The way forward

The effective and efficient way forward for Government is to aim to have a men’s health strategy and a women’s health strategy working in parallel. A complementary approach for men and women will help ensure that everyone gets the better, more tailored and effective services they need and deserve. To ensure any strategy is robustly founded, we are calling on the Government to start by establishing a ministerial men’s health taskforce – in the same way as it did for women’s health – to work at pace to:

- Bring together policy makers and the statutory and voluntary sector

- Produce a report on the state of men’s health in consultation with health professionals, organisations who work with men and the wider public

- Develop an action plan for the introduction of a Men’s Health Strategy

The need is urgent and the opportunity is huge. The time for action is now.

Join the campaign